Ascii Art History

ASCII art is a graphic design technique that uses computers for presentation and consists of pictures pieced together from the 95 printable (from a total of 128) characters defined by the 1963 ASCII Standard. Some Ascii art uses ASCII compliant character sets with proprietary extended set of characters (beyond the 128 characters of standard 7-bit ASCII). The term is also loosely used to refer to text based visual art in general. ASCII art can be created with any text editor, and is often used with free-form languages. Most examples of ASCII art require a fixed-width font (non-proportional fonts, as on a traditional typewriter) such as Courier for presentation.

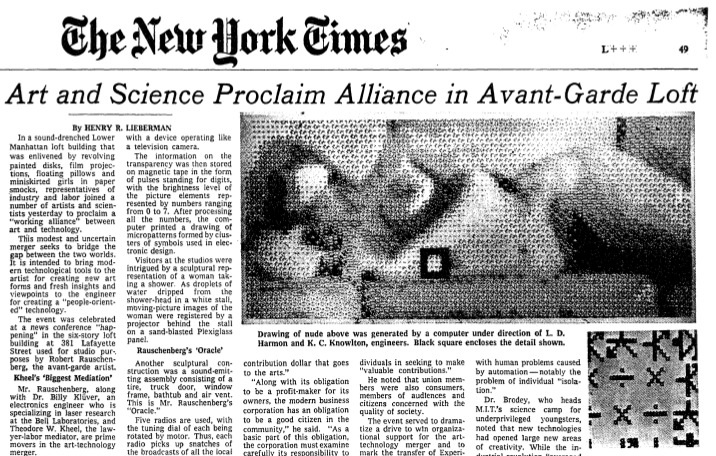

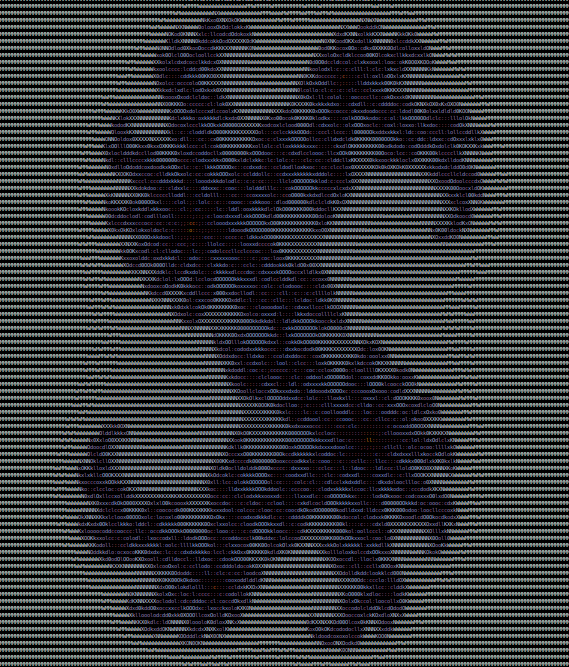

Among the oldest known examples of ASCII art are the creations by computer-art pioneer Kenneth Knowlton from around 1966, who was working for Bell Labs at the time. “Studies in Perception I” by Ken Knowlton and Leon Harmon from 1966 shows some examples of their early ASCII art.

ASCII art was invented, in large part, because early printers often lacked graphics ability and thus characters were used in place of graphic marks. Also, to mark divisions between different print jobs from different users, bulk printers often used ASCII art to print large banner pages, making the division easier to spot so that the results could be more easily separated by a computer operator or clerk. ASCII art was also used in early e-mail when images could not be embedded.

Pre-Computer Text Art

Concrete Poetry

Text art predates computers. Perhaps the earliest use of characters in art was in ancient Greece during the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE with shaped or patterned poems referred to as “concrete poetry”. In this art form, the words of a poem are arranged in such a way as to depict their subject.

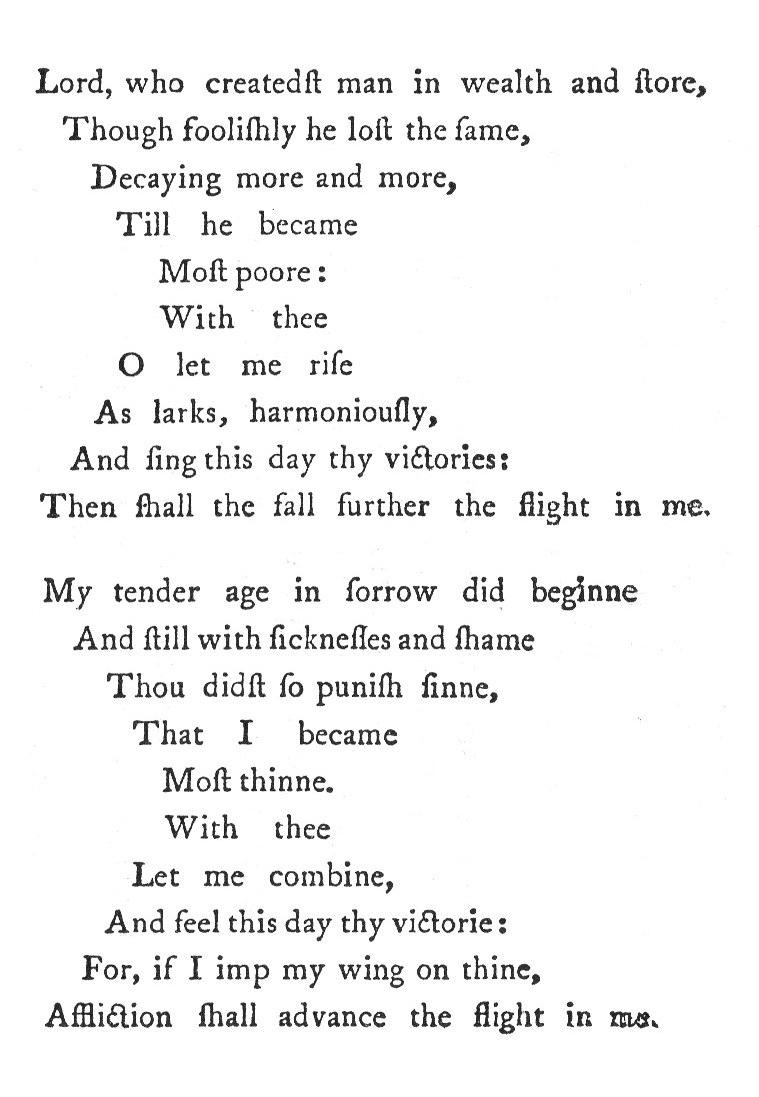

Early religious examples of shaped poems in English include “Easter Wings” and “The Altar” in George Herbert’s The Temple (1633):

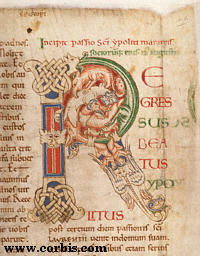

In the beginning, the written word did not consist of “text”. The first written documents consisted of pictures or glyphs which represented ideas and objects, not letters or text characters.

Over time, the written word developed into symbols which looked more like present-day text. The very first text art pictures were drawn by hand. Creative people used ornamental penmanship to create wondrously beautiful documents and pictures. The monastic monks created breath-taking manuscripts which incorporated letters of text into their art. However, there were few other pieces of art that were made from text characters.

Ironically, Ascii Art turned the arc of its own history back on itself, from the beginning when documents were written with pictures to pictures written as a text document.

Typewriter Art

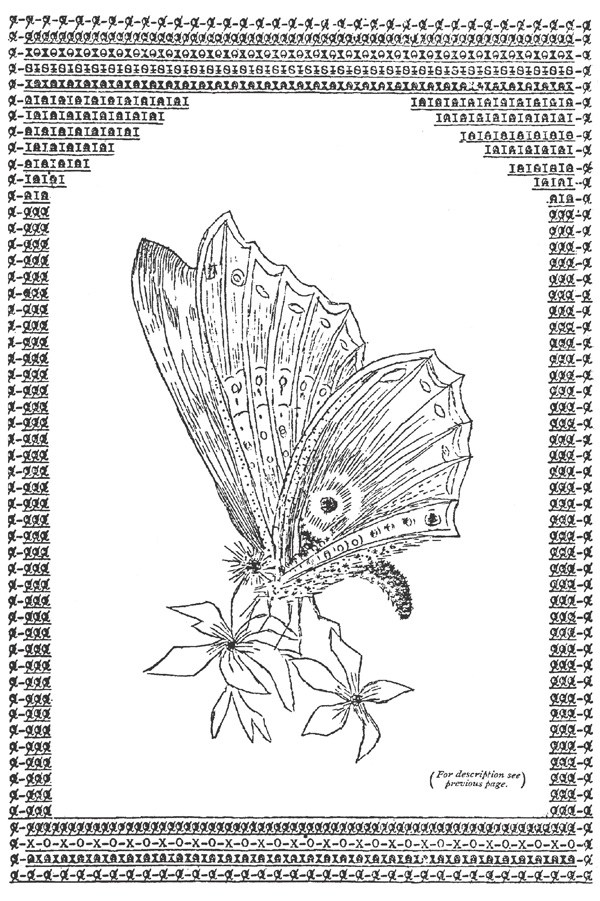

Text artists in the 19th century invented a novel technique for creating art: feeding paper into the rollers of typewriters numerous times, each at a different angle to allow the overprinting and fine-tuning of an image.

Teletype Art

Typewriter art was succeeded by Teletype art using character sets such as the Baudot code which predated ASCII. Text images produced on a TTY or RTTY have been discovered as early as 1923.

Computer Generated Text Art

Line Printer Art

In the 1960s Andries van Dam and Kenneth Knowlton were producing realistic images using line printers by overprinting several characters on top of one another. This technique used EBCDIC rather than ASCII. Line printer art flourished throughout the 1970s as anyone who had a job in a computer lab back then will tell you. Everybody learned how to print a Snoopy banner.

ASCII Art

In the late 1970s and early 1980s computer bulletin board systems, email users, game designers, Usenet news groups, and others began using ASCII art to represent images. ASCII artists invented Emoticons, short small combinations of characters which represented the user’s emotional state - happy, sad, angry, and more. Email messages and Usenet newsgroups were littered with :) and {:> and the Golden Age of ASCII art flourished throughout the 1990s.

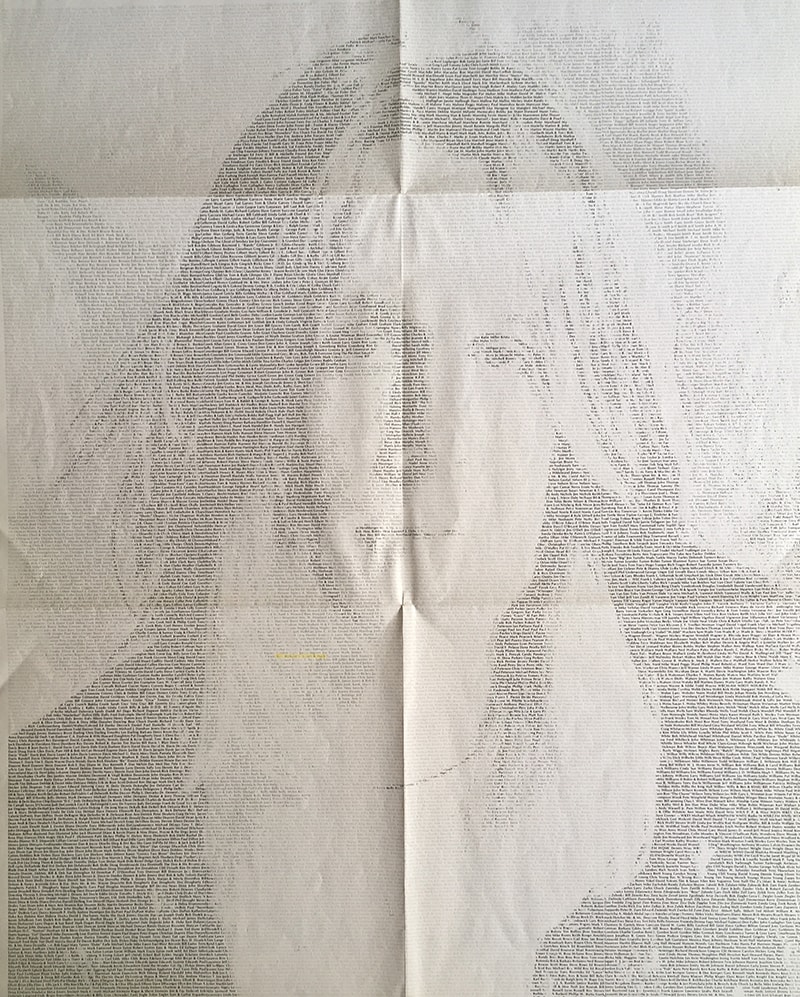

As usual, recording artist Todd Rundgren was out ahead of the wave on this phenomenon as well. In 1974 Rundgren released the double album “Todd” which contained a poster insert portraying Rundgren’s head composed of a list of names of fans that had sent back the postcard included within the sleeve of his previous release, “A Wizard, a True Star”. Rundgren had created the Ascii Selfie.

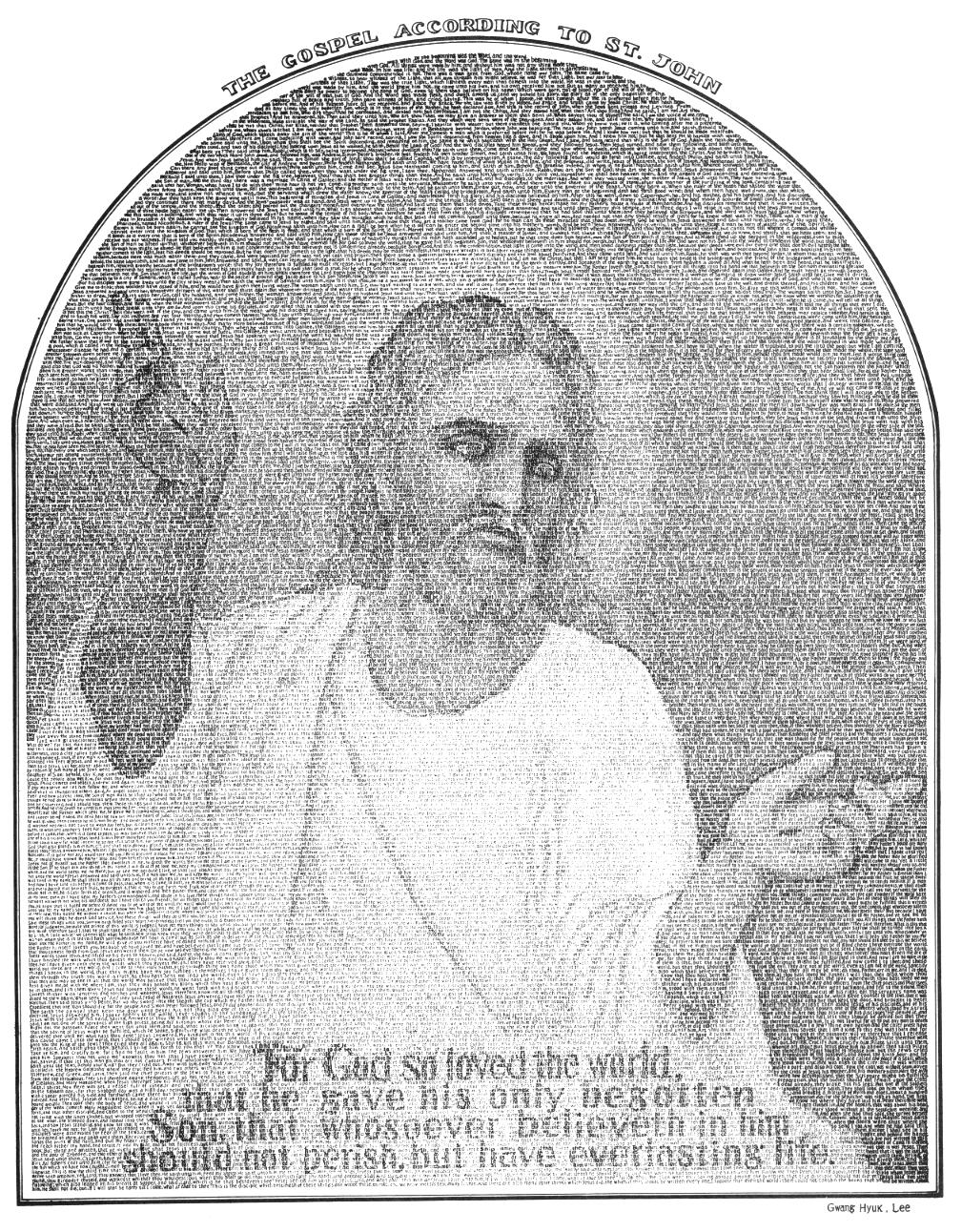

Todd was not the first Ascii Artist to render a portrait in text. During the Korean War (circa 1950), a very talented Korean named ‘Gwang Hyuk Lee’ made a hand drawn text picture depicting Jesus. He used the entire text in the Bible’s “Book of John” to create this image.

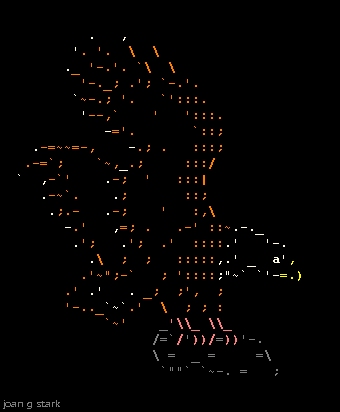

In the mid-1990s many Ascii Artists flourished online. One such artist, Joan G. Stark, also known by her pseudonym ‘Spunk’ or her initials ‘jgs’, was particularly prolific and talented. From 1996 to 2003 Stark created several hundred works of art, most of which were posted to the Usenet newsgroup alt.ascii.art. Between 1996 and 1998 her website received over 250,000 unique visitors. Stark’s involvement in ASCII art has been taken as an example of increased online participation by women, and her imagery as an example of ASCII art becoming “softer, more stereotypically feminine.”

Spunk’s website on Geocities is defunct but has been archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20091028050914/http://www.geocities.com/spunk1111 where one can still find what is perhaps the most extensive history of ASCII Art ever produced.

This technique of representing images as text found its way into the source code of computer programs as a way to represent company or product logos. In some cases, the entire source code of a program is a piece of ASCII art. For instance, an entry to one of the earlier “International Obfuscated C Code Contest” is a program that adds numbers, but visually looks like a binary adder drawn in logic ports.

ANSI Art

ANSI art is similar to ASCII art, but constructed from a larger set of 256 letters, numbers, and symbols — often referred to as extended ASCII. ANSI art also contains special ANSI escape sequences that can be used to color text.

The Decline of ASCII and ANSI Art

The rise of the Internet and graphical desktop environments saw the decline of BBSes and character based user environments which made ASCII and ANSI art harder to create and to view due to the lack of software compatible with the new dominant operating system, Microsoft Windows.

By the end of 2002 all traditional ANSI art groups like ACiD, ICE, CIA, Fire, Dark and many others were no longer making periodic releases of artworks, called “artpacks” and the community of artists almost vanished.

The Resurrection of ASCII and ANSI Art

ASCII and ANSI art resurrected in 2022 with the publication of “Asciiville”, a compendium of art, animation, utilities, and integrated components all utilizing character based graphics. Haha! Just kidding :smiley:. Asciiville leverages the resurgence of interest in character based graphics accompanied by many recent advances like Figlet Fonts, Lolcat, lsd, asciimatics, asciinema, btop, jp2a, Moebius, and more. These modern utilities and character based components have breathed new life into the ASCII art community and produced many interesting works of art and animation.

Appendix

Jim Boulton has written a fascinating article on the history and restoration of Computer Nude from Ken Knowlton and Leon Harmon’s “Studies in Perception I”. He provides the technical details of the artwork’s construction along with some great historical tidbits:

Computer Nude was made at Bell Labs on an IBM 7094, a $2 million investment at the time. A black and white photograph of the dancer and choreographer Deborah Hay was reduced to a grid of grey squares. Symbols from a telephony circuit diagram were then assigned to the greyscale values of those squares.

The resulting 12 feet by 5 feet print was hung on the wall at Bell Labs. Causing outrage, it was removed after a single day. Harmon and Knowlton were told not to associate the name of Bell Labs with the artwork in any way.

Robert Rauschenberg was more impressed, using the image as the backdrop to his press conference when he launched E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology). It was subsequently reproduced in The New York Times, becoming the publication’s first full-frontal nude. Bell Labs put it back on the wall.

Of interest to Kubrick fans, the photographer who took the original photograph of the model used in Computer Nude was Max Matthews. In 1961, Matthews programmed the same IBM 7094 (later used to generate Computer Nude) to play snippets from the song “Daisy Bell”. Arthur C Clarke was visiting Bell Labs at the time and incorporated the rendition into “2001: A Space Odyssey”. This was the computer that made the first computer nude AND it was HAL’s voice singing “Daisy”!!!